Industry and Labour

- Home

- Industry and Labour

INDUSTRY AND LABOR FORCE

In Afghanistan today, the goal is one and the same for achieving food self-sufficiency, achieving connectivity with the Eurasian development drive, and building a modern industrial base and skilled workforce. Actions in any one area, compel and reinforce the others. The tasks are hard, but straightforward, and moralizing after decades of enforced poverty and non-development.

Moreover, the “economic cooperation belt” around Afghanistan is functioning, as pledged in China March 31, 2022, by the Meeting of the Neighboring Nations of Afghanistan. This is apparent in trade, joint infrastructure projects, power supplies, educational programs, as well as in humanitarian aid, and in many different kinds of ways, as are reported below by economic sector.

STARTING POINT

The Afghanistan Chamber of Industry and Mines reports that as of summer 2022 there are only 6,000 factories active in the country, a very limited number in a population of 40 million, and many of the enterprises are small. This is the starting point.

What technically classify as core heavy industry sectors—steel, fabrication, assembly plants, cement works–are very limited. This situation reflects the fact that 85 percent of the population is directly or indirectly involved in agriculture, producing and processing their own food. That is their occupation, and therefore, the productivity of the economy as a whole of the nation is below what is needed to sustain the population.

Labor statistics, accordingly, show a very small section of the labor force employed. For 2020, the UN International Labor Organization, based on the Afghanistan Labor Force Survey, reported that the total employment in Afghanistan was 6.079 million. Contrast this to the total potential labor force which ten years ago was put at 11.59 million (in 2012). The employment figures are outside the gigantic informal economy (including drug-related activity), escaping all official statistics, but estimated at between 50 to 80 percent of GDP! Thus, such statistics are not the starting point.

Of the 6.079 million total employed workers in 2020, manufacturing was only 500,000, agriculture was 2.714 million and the remaining 2.865 million in public and other sectors. Moreover, the largest sub-sector of manufacturing was 348,000 million workers in textiles and garment-making. This reflects the activity in carpet-making, the unique, traditional craft for which Afghanistan has long been famous. Much of it goes on in home-settings by women and girls, with men tending the flocks and preparing the wool.

The objective is to take measures to expand the economy in the heavy and light industry sectors at the same time. A flagship integrated metal works is called for, and support for other core heavy industry sectors. On the light industry side, there are several obvious sub-sectors for rapid expansion. There is the huge demand for inputs for water management infrastructure—fixtures, gates, gauges, etc. All food and fiber processing sectors must be expanded from grains, dairy, meat, fish and produce, to hides and leather goods.

This calls for a rapid increase in the size of the manufacturing labor force across the board. The goal is to have 1.5 million manufacturing workers within the first four years, and in a second phase, reach the level of 4 million, at the same time lifting the skill level and forging the power of labor.

Cement

Cement/concrete is used in some way to build every kind of basic infrastructure, from road culverts to housing, hospitals and factories. But Afghanistan produced only 93,800 tons (in 2019) and most of its cement consumption is imported, 99 percent from Pakistan and Iran. For reference, China— the construction powerhouse, produces three times as much cement in an hour, as Afghanistan’s 94, 000 tons a year.

Cement/concrete is used in some way to build every kind of basic infrastructure, from road culverts to housing, hospitals and factories. But Afghanistan produced only 93,800 tons (in 2019) and most of its cement consumption is imported, 99 percent from Pakistan and Iran. For reference, China— the construction powerhouse, produces three times as much cement in an hour, as Afghanistan’s 94, 000 tons a year.

What’s needed is to increase output at the existing four cement plants, and start up new operations. The cement works are at Herat, Kabul and two to the north of Kabul. The basic inputs are abundant in Afghanistan—gravel, limestone, aggregate. But water is an issue, trucking must be expanded, and electricity is a chokepoint. There have been talks in the past few years of new cement plant ventures, but now is the time to get them going.

The aim is to build a series of cement plants with a total combined production capacity of 2.5 to 3 million tons per year. Each plant requires approximately 20 months from Greenfield to start of production. The target locations can combine the presence of all of the elements needed, from water and electricity, to the rock components required.

Steel

Vastly more basic steel-producing capacity is required for an infrastructure-led drive to build the economy. The Director of the Chamber of Industry and Mines in Kabul, Mohammad Karim Azimi reported in April, 2022, that 40 to 50 steel plants of various sizes are at work, by scrap-smelting, which, taking just the present day limited demand, makes the nation he said, “self-sufficient.” However, for launching large infrastructure construction, and general manufacturing, there is woefully not enough. The annual steel output of Afghanistan, in the range of 33,000 metric tons— as of 2018, must be increased many times over.

The fact that in recent times, Afghanistan is still exporting steel to Pakistan is no sign of adequacy of national production. Rather, it reflects, not only the low domestic steel consumption, but the fact that tons of metal scrap from the debris of decades of US/NATO operations in Afghanistan is still going into the Afghanistan re-smelting furnaces. The only hold-up has been the electricity shortages. It’s time to build the new, integrated steel works capacity to build the new Afghanistan.

Machinery and Machine Tools

Machinery—to make products ranging from vehicles to appliances to bridges—and machine tools to make machinery, are sectors requiring top-down support to get established and take off on the scale needed. Over the recent decades there are ventures of note, such as the steel and farm equipment manufacturing done in Nangarhar Province, and examples from Herat. In Kabul, a venture firm in 2020 began manufacturing gas, battery- and solar-powered small passenger vehicles. To scale up across all types of manufacturing, and supply the parts to sustain their functioning, machine tools are essential. There is no industrialization possible without this.

Machinery—to make products ranging from vehicles to appliances to bridges—and machine tools to make machinery, are sectors requiring top-down support to get established and take off on the scale needed. Over the recent decades there are ventures of note, such as the steel and farm equipment manufacturing done in Nangarhar Province, and examples from Herat. In Kabul, a venture firm in 2020 began manufacturing gas, battery- and solar-powered small passenger vehicles. To scale up across all types of manufacturing, and supply the parts to sustain their functioning, machine tools are essential. There is no industrialization possible without this.

The proposal is for ten machine-tool parks to be established in the key locations across the country, each with 10 to 30 workers, under the direction of a highly skilled machine tool operator/teacher. This will require some 200 quality machine tools. The program will be coupled with the key machinery-using industries, from vehicles, to chemical works, to farm machinery, food processing, furniture manufacture, etc. The source nations for both instructors and the machine tools to start the program, include Germany, Italy, China, the U.S. and others. The student/engineer trainees will need to work at the centers, and in related industrial settings, for up to five years, to master the high skills involved, and finally initiate a domestic machine tool capacity.

Light Industry

Targeted support for light industry has big payoff in jobs and output.

- Food processing is a wide open category for expansion, from flour milling, to storage and packaging of fresh fruits and vegetables for national consumption and export, as well as meat, and dairy processing (pasteurization and packaging).

- The sheep and wool sector involve processing from the fiber end to the hides and leather goods sector.

- Moreover, there is need for these types of light industry at urban centers in all parts of the country to support the increasing agriculture output.

- In Herat is an expanded industrial park whose factories will package agricultural goods, according to an announcement in June by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MoCI). Nooruddin Azizi, Minister of the MoCI visited the Herat industrial park, pointing to other kinds of factories opening there also, for example, a manufacturer of oxygen tanks. The output of tanks is expected to be enough to supply the entire western half of the nation. Azizi is calling on Afghans abroad to invest in expanding manufacturing. Some 20 percent of Herat factories have reopened in three to four months, and more are expected to do so by the end of the year, according to the Herat Chamber of Commerce and Mines.

- The government is working on the electricity reliability problem. The Herat industrial park has been limited by having only 10 hours of electricity a day, which is to be increased to 12 hours daily.

Since 70 percent of Afghanistan’s electric power is imported, allocation of scarce supplies in the short term is critical, but as power is increased—from imported sources at present, and eventually produced domestically, all economic activity will level upward.

ABUNDANT NATURAL RESOURCES

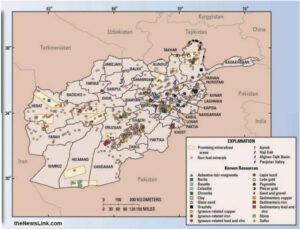

As already described, the resource base in Afghanistan is rich in minerals, ores, hydrocarbons and other valuable deposits, favorable to full-set industrial development. Afghanistan has an estimated 2.2 billion tons of iron ore reserves, placing the nation in the world’s top ten for extractable iron. The copper deposits are also immense.

As already described, the resource base in Afghanistan is rich in minerals, ores, hydrocarbons and other valuable deposits, favorable to full-set industrial development. Afghanistan has an estimated 2.2 billion tons of iron ore reserves, placing the nation in the world’s top ten for extractable iron. The copper deposits are also immense.

- Of special value are the rare earth minerals, including lithium, tantalum, and beryllium. All these metals are necessary for modern electronics, medical appliances and high-technology uses.

- The vast iron reserves are a dramatic asset, awaiting development. In October, 2022, IEA First Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar announced that iron mining rights would be put up for bidding soon, stressing the importance of the role of the industrial sector in the development of the country.

- The copper mine at Mes Aynak is one of the largest in Asia. People have been producing copper here since the Bronze Age. The ancient site has artifacts going back 3,000 years, and was home to an extensive Buddhist center with monasteries and many imposing features, whose remains should be preserved during mining. Since 2008, the China Metallurgical Group (MCC) has held a 30 year lease, for development of copper extraction. Getting this copper flow started will be a flagship project in the nation. China pledged in March, 2022, as stated in the Tunxi Initiative from the Meeting of the Neighbors of Afghanistan: “China supports its enterprises in investing and starting businesses in Afghanistan when the security situation permits, and in resuming projects such as the Aynak Copper Mine and the Amu Darya Oilfield in due course.”

- This oil and gas field in the north of Afghanistan, is in the basin of the Amu Darya River, in the same geological formation that is producing gas and oil for Turkmenistan. Its oil and gas will be a boon for the industrialization process in Afghanistan. In Fall 2022, the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum was in discussions with the Chinese firm CNPCI about the terms for going ahead with a refinery in the Qashqari region of the Amu Darya Basin.

- Coal mining is underway in Afghanistan, and can be expanded as required. It is exported to Pakistan, and talks were underway in October 2022, for exports to Iran. Afghanistan has 70 million tons of proven coal reserves.

SKILLED WORKFORCE

Training

Industrial skills and arts are part of the education drive in order at all levels, along with agriculture, health care, transportation, energy and general education. Parallel to the farm and pastoral training through agriculture extension programs from colleges, government and private institutions, industrial outreach and internship programs are critical for upgrading the skill level of the whole society.

Industrial skills and arts are part of the education drive in order at all levels, along with agriculture, health care, transportation, energy and general education. Parallel to the farm and pastoral training through agriculture extension programs from colleges, government and private institutions, industrial outreach and internship programs are critical for upgrading the skill level of the whole society.

A good example of the varied aspects of this, is the revival of silk production. In 2014, a training center was established for 1,250 women of the Zindajan district on the edge of Herat, for making silk, from beginning to end. They raise the silkworms from eggs, feeding them mulberry leaves from the trees surrounding the city. They harvest and dry the silkworm cocoons, and spin the silk thread by hand, in a month long process. They weave the precious thread into traditional Afghan carpets, scarves and other apparel. The project also trains the workforce in marketing their silk products, specifically in Italy. Today, nearly 4,000 women produce silk in Zinajan.

Neighboring Nations

Specialist education abroad for Afghan students is a priority, and the last meeting of Afghanistan’s neighbor nations, March 31, 2022, in China, addressed this as “Capacity Building” in its April 1 “Tunxi Initiative of the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan Supporting Economic Reconstruction in and Practical Cooperation with Afghanistan.”

Nations made individual pledges, for example, “China is ready to work with other neighbors of Afghanistan to provide joint training programs for Afghanistan.” And, “Russia pledges to further provide scholarships to Afghan students.” “Tajikistan will continue to create favorable conditions to those Afghan students studying in its higher education institutions, as well as allocate annual scholarships to the citizens of Afghanistan.” Pakistan, Iran and Turkmenistan spelled out their readiness likewise.

The Tunxi Initiative concludes by returning to the fundamental point that world backing is required for a new, modern Afghanistan. “All parties call on the international community, as well as relevant regional and international financial institutions, to provide financing support for Afghanistan’s reconstruction and development.” (infr. foreign relations section)

SPECIAL PROJECT

In all national development plans, there are certain key projects that drive the whole process, in particular, that involve upgrading the workforce in many fields, and that create demand for industrial output. Among those in Afghanistan are the Trans-Afghan Rail Corridor, described in the connectivity section, the Mes Aynak copper project, and the reinvigoration of the Kabul Polytechnic University (KPU).

Trans-Afghan Rail Corridor

Field work is underway on this 573 km corridor (the Afghanistan span), providing rail service through six provinces, including Kabul, the capital, with a combined population of 9.5 million. The route traverses three major river basins, including the very productive northern agriculture region, connecting it to major cities from Mazar-i-Sharif, to Kabul, to Jalalabad, which, among others, are areas of expanding industrial parks. The “Kabul Corridor,” as it is also called, should be the starting point for a national rail grid. Its manifest usefulness is that it connects with all Eurasia, via Uzbekistan in the north, and Pakistan in the east. The opportunity for direct training in construction, engineering design, bridge and tunnel building, and metal-working, trucking and other skills is huge, as is seen in the impact in other multi-nation mega rail projects, for example, the China-Laos Railway. The new opportunities for factories, both light and heavy industry, are likewise outstanding.

Mes Aynak Copper Mine Project

The Mes Aynak (“Little Copper”, in Dari) site is just 40 km southeast of Kabul, and a location of great historical importance. The China MinMetals Corporation (CMMC), which holds the development lease, originally signed in 2008 as a 30-year contract by predecessor Chinese firms, has not yet begun the project, under years of uncertainty and turmoil. But conditions now being favorable, the terms of the agreement include features very important to the impetus for overall national development. There is to be a railroad connection built, and also a coal-fired power plant, making use of Afghan coal deposits. These components, along with the ore-smelting and general construction requirements, in addition to mining operations, present wide opportunities for workforce development and secondary industrial projects.

A special challenge here in Logar Province, is to preserve the significant archeological treasures that must be properly cared for. There are extensive remains of a remarkable Buddhist city here in the period 200 CE to 700 CE (for more, see the section on cultural heritage). These must be preserved, either on site or outside the mining area. This responsibility is not a constraint, but a challenge, and a skills-training opportunity for a nation on the move to, once again, take its place at the center of the Eurasian Silk Road.

Kabul Polytechnic University

This higher-learning institution, considered the main center of educating engineers in Afghanistan, should be massively expanded.

This higher-learning institution, considered the main center of educating engineers in Afghanistan, should be massively expanded.

Built in 1963 with Soviet help, and more recently staffed by various US universities and agencies, KPU is the basic center of training for professional engineering cadres in Afghanistan that has trained thousands of specialists in essential professions.

The wide-ranging areas of study include civil and mechanical engineering and construction, architecture, geology, exploration and mining, chemical technologies, engineering geodesy, autos and tractors, power supplies for industry, and many more.