Transport And Connectivity

- Home

- Transport And Connectivity

CREATING AN INTEGRATED NATIONAL ECONOMY

Afghanistan figured prominently in the cross-traffic of the ancient Silk Road, when most goods were carried first by donkeys, and later by camels, in contrast to its present-day lack of transportation infrastructure. Unlike its neighbors, where colonial powers Britain and Russia built grand railway projects, Afghanistan’s leaders, more than a century ago, resisted the railway age, out of fear of imperial conquest.

It was only late in 2010 that the country’s first real railway track was completed: a 75-km (47- mile) route linking the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif to the Uzbekistan border. However, as it happened, at that very same time, a number of other rail line proposals were made, but most all were throwbacks to the old colonial type.

In September 2011 a thorough report was issued on the fabulous natural resource base of the country, done by the U.S. Geological Survey, which confirmed what the Soviet geologists knew years before. Afghanistan sits atop huge deposits of copper, iron, marble, gemstones, rare earth minerals, coal, gas, and much more. The country is one of the world’s most resource-rich nations, whose mineral wealth is estimated at $3 trillion.

In 2011, the European Union and the Asian Development Bank proposed building rail lines stretching mainly from specific mining sites to Afghanistan’s borders, in the name of “development,” exactly typical of neo-colonial rule.

Now, things are set to change. A massive investment in the mechanization and modernization of agriculture will free a growing workforce for other productive sectors lacking manpower. Part of them will find employment in local and regional agro-industrial centers coming into being. Others will be welcomed to get training as teachers, health workers, doctors and engineers, at regional and national universities. Still more farm youth will go into construction, and others into the heavy industry sectors of steel works, copper refining, and other metallurgical complexes, some to be erected directly close to the mining sites.

As in China, thousands of Afghan citizens will have productive places to go, rather than ending up in the informal economy on the streets of Kabul. They will be invited—by better wages and good prospects—to relocate to the new industrial centers. No imports—not a single loop of copper wire, not a single ton of steel—need come in from abroad, since Afghanistan will be producing them all at home. This national goal of productivity is the process to be served by any national transportation grid, energy grid and road grid—all of them at present, close to non-existent. The objective is to serve an integrated national economy, rather than a patchwork of regional centers, oriented for survival only by dependence on narrow, cross-border import-export flows.

THE HEART OF EURASIA

The concepts and the momentum are in place, nationally and internationally, to muster the resources and build the ground, air, pipeline, power, digital and all modern conveyance systems for not only a national economy, but also for the full participation in regional and continental growth.

The concepts and the momentum are in place, nationally and internationally, to muster the resources and build the ground, air, pipeline, power, digital and all modern conveyance systems for not only a national economy, but also for the full participation in regional and continental growth.

Afghanistan is centrally located for maximum connectivity with the new development projects in Eurasia from the collaborative framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Eurasian Economic Union, the Council of Turkic States and others.

Afghanistan formally joined the Belt and Road Initiative in May 2016, during a visit by Chief Executive of Afghanistan, Dr. Abdullah Abdullah to China, in which the Afghan and Chinese Foreign Ministers signed a Memorandum of Understanding on cooperation under the BRI. The Afghan Foreign Ministry stated than that, “Given its location at the crossroads of Central, South, and Southwest Asia, Afghanistan is well placed to partner with China and connect to the wider region via BRI.”

- Afghanistan is positioned in between two of the major BRI corridors in Eurasia: the ChinaCentral Asia-West Asia Corridor; and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor;

- Afghanistan also became a member in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2017. However, due to the situation in the country, and obvious U.S.-China antagonism, no infrastructure or other projects were launched jointly;

- Afghanistan has shown its desire to become a member of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa,) to which Iran has already applied for membership.

Most importantly, there have been three meetings so far of the Foreign Ministers among the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan, first convened in China (online) Sept. 8, 2021, which has formed a new mechanism for collaboration in Afghanistan economic development.

The Third Meeting on March 31, 2022 in Tunxi, Anhui Province, produced concrete pledges about connectivity throughout the region, in the overall “Tunxi Initiative” that the attending nations released. It stated, “All parties recognize the importance of connectivity to the sustainable development of Afghanistan as a ‘land-locked country,’ and stand ready to leverage their respective strengths to support Afghanistan in, based on the existing transportation networks with neighboring countries, exploring step by step new convenient channels to strengthen ‘hard connectivity’ of infrastructure, and ‘soft connectivity’ of rules and standards with neighboring countries.” (From April 1, 2022 document, “The Tunxi Initiative of the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan on Supporting Economic Reconstruction in and Practical Cooperation with Afghanistan.”) Uzbekistan will host the Fourth Meeting of the group in early 2023.

There are other historical points of reference, backing today’s launch of transportation projects. Almost one year ahead of the U.S. and NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reached a nine-point consensus at the Inaugural China-Central Asian Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting July 16, 2020.

There are other historical points of reference, backing today’s launch of transportation projects. Almost one year ahead of the U.S. and NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reached a nine-point consensus at the Inaugural China-Central Asian Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting July 16, 2020.

Of interest here is point three, which states that the parties will make more efforts to ‘synergize the Belt and Road Initiative and the development strategies of Central Asian countries, expand trade and provide more common ideas and concrete actions on the development of a Silk Road of Health and the Digital Silk Road.” Point eight explicitly concerned Afghanistan, stating, “China and Central Asian countries all support the peace and reconciliation process in Afghanistan and stand ready to play a constructive role in promoting intra-Afghan negotiation, restoring peace and stability, advancing Afghan economic recovery and strengthening regional cooperation.”

In June 2021, came another important development, the joint statement of the Fourth ChinaAfghanistan-Pakistan Trilateral Foreign Ministers’ Dialogue, stressing that, “the three sides reaffirmed that they will deepen cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative, Regional Economic Cooperation Conference (RECCA), ‘Heart of Asia/Istanbul Process’ (HoA/IP) and other regional economic initiatives.” Connectivity between the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and Afghanistan was a key element in this dialogue.

RECCA—Afghanistan Regional Economic Cooperation Conference–mentioned in the statement, is an initiative involving 11 nations, launched in 2005 in Kabul by the Foreign Ministry of Afghanistan, to agglomerate all the different proposals for connectivity and development corridors connecting Afghanistan to its neighbors and more distant regions. It has published several studies on these corridors—transportation, and conveyance routes for gas and electricity—and how they would serve the region. Now is the time for action.

EURASIAN RAIL CONNECTIVITY

The fact that two-thirds of the nation’s terrain is mountainous is a challenge for rail, as it has been for roadways for centuries, but not at all impossible. Japan, Switzerland and China have all shown the way on technologies to meet the challenge. The modern tunnel-boring machines are more efficient and cheaper than ever before.

The overview of the rail system program is for cross-country rail, as well as a national ring-route, connections with all six border nations, and special rail wherever required to serve new concentrations for activities that will be growing–mining, industrial, agricultural and tourism concentrations. Light rail, and underground subways in urban areas are also in order. A key investment for new rail, is to double track, to accommodate freight on one line, and passengers on the other. China has important innovations in this area, including dedicated, elevated tracks for passenger transport, atop ground-level freight lines, often built at an earlier time. There are also modal options, as seen in China for not only high speed rail, but magnetic levitation, and for cheap air-cushioned tracked vehicles.

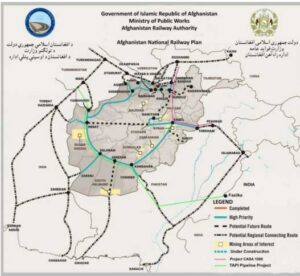

At present, there is no rail system in Afghanistan. There are three locations of rail lines, at border points for the transfer of goods, at Turkmenistan – Aqina and Torghondi rail lines, and at Uzbekistan – at Hairatan. All told, total track length is fewer than 400 km. But the priority projects are on the drawing boards.

Trans-Afghan Rail Corridor

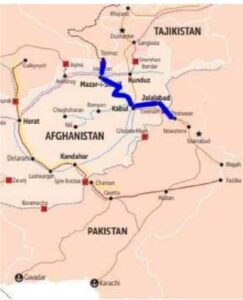

This flagship rail project, known also as the Kabul Corridor, cuts across the country from Uzbekistan to Pakistan. The line goes from Termez, Uzbekistan, to Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Balkh Province (already built), through the mountains to Kabul, thence to Peshawar, Pakistan, with through connections, south to Arabian Sea ports, and east and north, to the ChinaPakistan Economic Corridor. The crossAfghanistan distance is 573 km.

This flagship rail project, known also as the Kabul Corridor, cuts across the country from Uzbekistan to Pakistan. The line goes from Termez, Uzbekistan, to Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Balkh Province (already built), through the mountains to Kabul, thence to Peshawar, Pakistan, with through connections, south to Arabian Sea ports, and east and north, to the ChinaPakistan Economic Corridor. The crossAfghanistan distance is 573 km.

- In February, 2021, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Pakistan agreed on a joint plan to build the railroad, discussing an expected annual capacity to transport up to 20 million tons of cargo. The estimated cost at the time was US$5 billion;

- Uzbekistan President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has referred to the Trans-Afghan Corridor as “the project of the century.” In July, 2022 Kazakhstan President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev Said that his country “is ready to participate in the construction of the railway…In particular, we will continuously supply railway superstructures with materials and supply rolling stock.” A delegation from Uzbekistan went to Europe in October 2022 to Brussels and the Netherlands, to promote the project and seek funding and partners.

The impact of this trans-national line to support Afghanistan’s agriculture and industry, and raise living standards, will be transformational. The route crosses three main river basins, in which over 30 percent of Afghanistan’s population lives. It connects the country’s currently most productive agriculture zone with domestic and international markets both. There have been other proposed routes of merit, for crossing the nation, and linking to continental networks, but the Trans-Afghan Rail Corridor has momentum among all the many nations standing to benefit along with Afghanistan. For example, delivery time for freight from the Russian border ( Oxinki) to the port of Karachi will be reduced by 16-18 days

China-Afghanistan Rail Corridor

This train-line is already underway, except for a stretch by truck in Kyrgyzstan, until the railway there is completed. The train starts in China’s Xinjiang Province, going from Kashgar to Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan, where the container/cargo proceeds by truck, then by train through Uzbekistan, finally arriving at the Afghanistan border town of Hairatan. The trial run left Sept. 13, 2022 from Kashgar, and 11 days later arrived in Hairatan. This contrasts with the same cargo taking one to three months by sea from China to Karachi, then overland to Afghanistan.

This train-line is already underway, except for a stretch by truck in Kyrgyzstan, until the railway there is completed. The train starts in China’s Xinjiang Province, going from Kashgar to Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan, where the container/cargo proceeds by truck, then by train through Uzbekistan, finally arriving at the Afghanistan border town of Hairatan. The trial run left Sept. 13, 2022 from Kashgar, and 11 days later arrived in Hairatan. This contrasts with the same cargo taking one to three months by sea from China to Karachi, then overland to Afghanistan.

Special Envoy to Afghanistan Yue Xiaoyong said in July, 2022, “Beijing sees Afghanistan as a bridge linking Central and South Asia.” He praised the multi-national ChinaAfghanistan Rail Route, while also expressing China’s support for the proposed Trans-Afghan Rail Corridor.

Lapis Lazuli Transit Corridor

This multi-modal line, named after the lustrous blue gemstone for which Afghanistan is famous, connects Afghanistan through Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, to the Black Sea and Turkey, and thence to the Mediterranean.

The agreement to create the corridor was signed November 15 , 2017 by these nations, and the line went operational at the end of 2018.

The corridor starts by rail from the Afghanistan land ports of Aqina in Faryab Province, and Torghundi in Herat, going to the Turkmenbashi Port in Turkmenistan, across the Caspian Sea to Baku, and on to the Black Sea ports of Poti and Batumi in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. Through Turkey’s ports and overland, the cargo can proceed to Europe.

In November, 2022, Afghanistan shipped its first cargo of pine nuts from Herat to Germany via the Lapis Lazuli Corridor. The Ministry called it, “The first huge shipment of up to 12 tons of pine nuts worth US$400, 000,” and it will be repeated.

The Five Nations Railway Corridor

This 2,100 km route is a BRI initiative that will run through five nations in Central Asia, from Iran in the west, through Afghanistan eastward, to Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and finally China. Afghanistan is to have about half the rail length. For example, the track route between Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif is 657 km long.

This 2,100 km route is a BRI initiative that will run through five nations in Central Asia, from Iran in the west, through Afghanistan eastward, to Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and finally China. Afghanistan is to have about half the rail length. For example, the track route between Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif is 657 km long.

Thus, not only does the FNRC provide multi-national east-west through-transit, but going through Afghanistan’s northern region of agriculture productivity, hydrocarbon deposits, and population density, it will give great support to Afghanistan’s national development platform.

When completed it will link Afghanistan with Iran’s southern ports, and link China to Turkey. The Afghanistan Railway Authority (ARA) announced the first week in November, that the construction of the Khawaf-Herat Railway—part of the Five nations Railway Corridor– will be completed by the end of November.

This 225 km-long cross-border section links Khaf in the northeastern Iran Province of Khorasan Rzavi to Herat, the center of Herat Province. The ARA announced it will soon have a delegation in Iran to make plans to open up commodity shipments, especially minerals exports to Iran.

The Chabahar Corridor

The Chabahar port in Iran is the deep sea outlet for the multimodal International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), for which Afghanistan is connected through the Chabahar Corridor, known as the ITTC (International Transport and Transit Corridor). The “Chabahar Agreement” was signed in May 2016 among Iran, India and Afghanistan for this purpose. Cargo can go back and forth from India through the port, in which India has investments, and can involve not only Iran and Aghanistan, but northward to Central Asia and Russia.

In October 2017, India sent the first wheat shipments to Afghanistan through the ITTC. India has invested in rail to the Afghan border—the Chabahar-Hajigaj railway. Within Afghanistan, Iran has invested in roadway to Kabul. The ITTC thus positions Afghanistan to intersect the 7,200 km long multi-modal International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) connecting to Turkey and Europe, and the Trans-Siberian Highway and rail lines across Russia. The development of Chabahar and ITTC has been inhibited by the U.S. sanctions policy, because, though technically the U.S.

Granted the port a waiver, no construction or logistics firms want to risk full involvement in building it up, under the geopolitical threats. This must end.

Cross Border Connections Other features of Afghanistan’s national rail program call for cross-border rail connections at key locations. For example, developing the railroad and cargo center in the Free Economic Zone of Panj on the Tajikistan-Afghanistan border, will be of mutual benefit.

Turkmenistan backs further implementation of the Turgundi-Herat Railway, which so far is 173 km. Turkmenistan has pledged to develop the route Atamyrat-Imamnazar-Akina-Andkhoy, and in general to promote the transport corridor Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan, with interconnections to China.

For the Future: Perimeter Rail

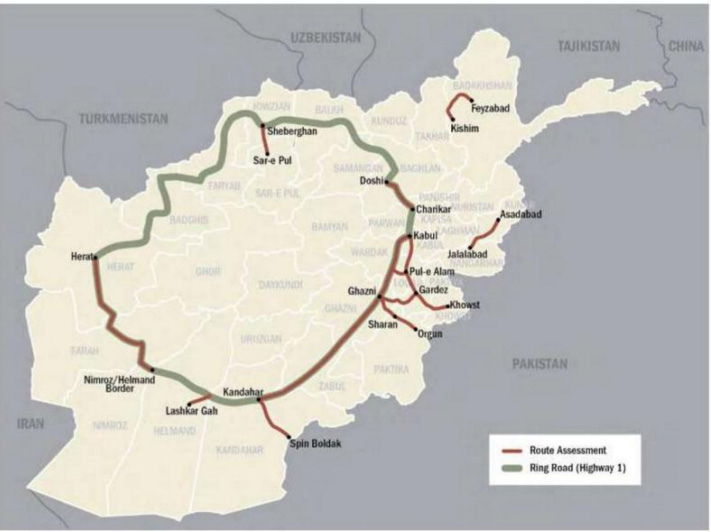

The productivity from these kinds of developments make a national perimeter rail line feasible, along the configuration of the Ring Road already in use, and whose upgrade will make it even better.

NATIONAL ROADWAYS

The existing road density in Afghanistan is a low 0.03 of road per sq km, and 0.88 km per 1,000 people which partially reflects that two-thirds of the nation is mountainous, but mostly reflects the impact of decades of lack of infrastructure building under foreign occupation and strife. The immediate task, in the transition to a fully modern transportation system, is to upgrade existing roads, and to build-out new roads in the near future. The existing road network does connect all the major population centers, and extends somewhat into remote areas

Ring Road

The national Ring Road of 2,200 km (1, 400 mi) of two-lane highway, was originally built in the 1960s, but since that time, the Ring Road has seen many sections fall into disrepair, and is underdeveloped.

However, major productivity gains for the nation can be accomplished by upgrading priority stretches, as well making other road improvements, including crossmountain roads, and especially the principal roads to the six nations bordering Afghanistan: Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, and even to China, through the remote Wakhjir Pass, in the Pamir Mountains.

Exemplifying this is the collaboration with Pakistan on the completion of the TorkhamJalalabad Road, and restoration of bus service between the two nations.

Road Upgrades

Construction has started on upgrading targeted roadways within Afghanistan. The task ahead is to increase this process, which means expanding the construction sector. Making road improvements requires developing the inputs, especially concrete and pavement materials, machinery and skilled labor crews. This then, creates the capacity for new road construction, as mining, industry and agriculture require. Work is currently underway on the Kabul-Herat highway, the long, 650 km (straight line) cross-country road. In the east, the Salang Road is being upgraded.

Transit Upgrades

In support of these “hard” connectivity improvements in road infrastructure, there are also supporting initiatives in “soft” connectivity. Four areas of this work were described in a new report from Kabul in September, 2022. The 25-page “Proposal for the Prioritized Projects of the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation” was issued by the Directorate of Planning, Research and Projects Implementation of the Ministry. The report addresses re-regulating road use and establishing toll gates; building transportation terminals to serve passengers and freight transit; building TIR parks (streamlining international cargo transit); and urban transportation, beginning in Kabul. The report gives specifics, for the purpose of letting private contracts for the work.

Transportation Terminals, Toll Gates

The government has a program to re-regulate roadways, including implementing a system of toll gates. The many objectives include deterring overloaded trucks, dangerous vehicles, and reducing damage to roadways.

A related program will construct “transportation terminals” at key points in the national roadway system, for the purpose of safe, reliable transit of agriculture and all other cargo, and to serve passenger travel. These terminals will be multi-purpose centers, designed to accommodate office space for transport companies, fuel stations and storage, vehicle parking, hotels and restaurants, repair shops, car washes and other amenities and services. All this is to improve “the safety and security of passengers, drivers, property and vehicles.” Other goals include relieving congestion in the cities, wasting time, deterring corruption, allowing collection of tolls, and many other obvious purposes.

The international border crossings will have special attention, according to the government’s priority, so they can have administrative and physical infrastructure that will facilitate transfer of goods in sealed containers, and obviate time-consuming border inspection, but still provide the necessary security guarantees for customs officials.

TIR Parks

There are eight border sites tentatively identified for what is called “TIR Parks,” which will oversee international road transportation under the 1976 international convention on international goods cargo covered by the Transport International Routier (TIR) procedures. These complexes, besides accommodating customs administration, will also have every kind of facility from hotels, fuel stations and police, to mosques and health clinics.

URBAN MASS TRANSIT AND AVIATION

The existing road density in Afghanistan is a low 0.03 of road per sq km, and 0.88 km per 1,000 people which partially reflects that two-thirds of the nation is mountainous, but mostly reflects the impact of decades of lack of infrastructure building under foreign occupation and strife. The immediate task, in the transition to a fully modern transportation system, is to upgrade existing roads, and to build-out new roads in the near future. The existing road network does connect all the major population centers, and extends somewhat into remote areas

Urban Mass Transit

Finally, the new Transport Ministry priorities address the need for urban public transit, beginning in Kabul, and then with designs for other cities. Kabul, for example, has 4.117 million people, with an estimated 900,000 vehicles circulating daily, in a chaotic way, with pollution and a big waste of time and energy. A system of mini-buses and large buses has been designed, to be purchased from Uzbekistan, and set in operation in a very orderly fashion.

As the process moves ahead, this is the opportunity for new technologies. Afghanistan could become a pioneer of especially air-cushioned tracked vehicle transport, operating on elevated or underground tracks. This is a relatively low cost, but high-tech solution currently developed by small start-up companies in Brazil and France.

Aviation

There are 46 airports in Afghanistan, four of which are international—Kabul, Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif. Over recent months, a number of them have had repairs and improvements, and certain key “Air Corridor” cargo trade routes activated. The airport system upgrade process is valuable in itself, for intra-Afghanistan connectivity; but it also supports international trade flows of high-value cargo, such as dried fruits, nuts, gemstones, and carpets, and supports cooperative foreign relations.

The Mazar-i-Sharif International Airport, for example, had renovation work completed in November, 2022, done by the National Electric Grids of Uzbekistan JSC. The lighting, signaling, runway and other features have been brought up to the level of modern requirements, so that international as well as domestic flights can take place. Various other arrangements are in place, for example, the U.A.E. Company GAAC is operating, under license from the Afghan government, the ground services for Kabul, Herat and Kandahar Airports.

The Pine Nut Air Corridor is carrying Afghan pine nut exports to China. The India-Afghanistan Air Corridor for trade, especially fruit exports, was re-opened in early November, 2022, after a hiatus beginning in August, 2021. In recent years, air corridor exports went to elsewhere in Central Asia, Russia, and Europe as well as China.

ENERGY

Electricity Transmission, Pipelines

The current and near-term phase of provision of electricity, oil and gas, and communications involves shared infrastructure and dependency on supplies from neighboring nations, until Afghanistan’s own supplies and infrastructure can be built up toward self-sufficiency.

There are a number of projects, outlined by the Afghanistan Regional Economic Cooperation Conference (RECCA) in 2018, and now urgent to fulfill, to better serve the mutual interests of Afghanistan and neighboring countries.

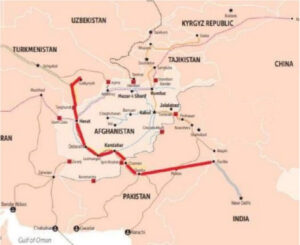

TAPI gas pipeline

The project for a pipeline to move gas from Turkmenistan, across Afghanistan and Pakistan to India is known as TAPI, also called the Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline. The first agreement was signed in 2010, sections have been built in Turkmenistan and Pakistan, and work is to commence as of Fall, 2022 in Afghanistan. The trans-country route is 1814 km, running from the Galkynysh gas field in Turkmenistan, through Afghanistan via Herat and Kandahar, across Pakistan to India. Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar said in a statement September 2022, “The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is completely ready to begin the TAPI project and is committed to any form of collaboration in this area.” The line is expected to supply about 33 billion cubic meters of gas per year, 5 bcm of which will be taken up in Afghanistan, with Pakistan and India each getting around 14 bcm. For future reference, there are also significant oil deposits in the north in the Amu Darya River Basin. Pumping had begun 10 years ago, but the project failed under the averse political-economic conditions. Now there are new prospects of success, with the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum negotiating new terms for with the Chinese company CNPC, to potentially start pumping within months. The oil is to be refined within Afghanistan. This raises the practical question of plans for new oil and gas pipelines.

The project for a pipeline to move gas from Turkmenistan, across Afghanistan and Pakistan to India is known as TAPI, also called the Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline. The first agreement was signed in 2010, sections have been built in Turkmenistan and Pakistan, and work is to commence as of Fall, 2022 in Afghanistan. The trans-country route is 1814 km, running from the Galkynysh gas field in Turkmenistan, through Afghanistan via Herat and Kandahar, across Pakistan to India. Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar said in a statement September 2022, “The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is completely ready to begin the TAPI project and is committed to any form of collaboration in this area.” The line is expected to supply about 33 billion cubic meters of gas per year, 5 bcm of which will be taken up in Afghanistan, with Pakistan and India each getting around 14 bcm. For future reference, there are also significant oil deposits in the north in the Amu Darya River Basin. Pumping had begun 10 years ago, but the project failed under the averse political-economic conditions. Now there are new prospects of success, with the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum negotiating new terms for with the Chinese company CNPC, to potentially start pumping within months. The oil is to be refined within Afghanistan. This raises the practical question of plans for new oil and gas pipelines.

TAP-500 and CASA-1000 electric power grid.

The TAP-500 kV Power Project is named for participants Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The concept is for Turkmenistan to supply electricity year-round to the other two neighbors, via transmission lines to be built, at a length across Afghanistan of 750 km. The plans call for Afghanistan to receive on average 1000 MW of electricity through the project. A memorandum of understanding was signed in 2015, and technical and equity proposals worked on in successive rounds of talks. Now is the opportunity to proceed.

The TAP-500 kV Power Project is named for participants Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The concept is for Turkmenistan to supply electricity year-round to the other two neighbors, via transmission lines to be built, at a length across Afghanistan of 750 km. The plans call for Afghanistan to receive on average 1000 MW of electricity through the project. A memorandum of understanding was signed in 2015, and technical and equity proposals worked on in successive rounds of talks. Now is the opportunity to proceed.

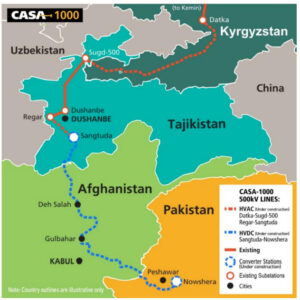

The CASA-1000 project refers to the Central Asia-South Asia Regional Energy Market. CASA1000 will wheel 1300 MW of electricity from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – during the summer months when they have a surplus – south into Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The original agreement was signed in 2015, and there is a four-nation CASA-1000 functioning at this time. Surveys and preparation have been done for the complex of power transmission infrastructure required.

There are connecting lines under construction in Pakistan and Tajikistan, but in Afghanistan, the financial crisis has deterred work. Facilitating Afghanistan’s national banking and credit system to function will see this project and others take off