Workshop G: Industry and Labour

- Home

- Workshop G: Industry and Labour

How to achieve full, productive employment; expanding heavy and light industries; new industrial zones; skilled labour training; exchange programs with Central Asia; feasibility studies for Mes Aynak copper zone. By Dennis Small, Department of Physical Economy, Schiller Institute, U.S.A.

Good afternoon. My name is Dennis Small, and I’m with the Schiller Institute in the United States. Thank you for inviting me to participate in this international deliberation on the prospects and strategy for bringing about the coming Afghan economic miracle. The issue of ensuring the full employment of a productive labor force, one with rising skill and productivity levels, is at the heart of the issues we are addressing in this conference.

Good afternoon. My name is Dennis Small, and I’m with the Schiller Institute in the United States. Thank you for inviting me to participate in this international deliberation on the prospects and strategy for bringing about the coming Afghan economic miracle. The issue of ensuring the full employment of a productive labor force, one with rising skill and productivity levels, is at the heart of the issues we are addressing in this conference.

The key areas of industry, both heavy and light, best suited for this programmatic approach include cement, steel, infrastructure construction, and metallurgy, all with an emphasis on training an increasingly skilled labor force in modern technologies.

What Is Real Unemployment?

Please note that I used the expression “real unemployment.” Allow me to explain what I mean by that, because that is our starting point to then suggest some solutions.

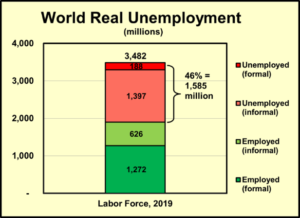

In May 2020, EIR magazine published a study which I led under the title “The World Needs 1.5 Billion New, Productive Jobs.” We looked at the level of real unemployment in the world by taking into account not only official unemployment, but also disguised unemployment and underemployment, especially in the so-called “informal” sector of the economy. We addressed this from the standpoint of the science of physical economy as developed by Lyndon LaRouche: productive employment means a person’s participation in the process of producing the physical goods, and related necessary services (such as health and education), required to increase society’s power to provide an improved standard of living and culture to a growing population. Having a “job” in the drug trade, or working in a Wall Street bank (which is often the same thing), is not productive labor: it doesn’t produce real wealth.

LaRouche’s approach is radically different than the standard, textbook definition, such as that of the World Bank, which defines employment as “any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit.” Notice that the only criterion here is a monetarist one: receiving monetary or related compensation for any activity. No distinction is made between earning $100 from building a house, engaging in criminal activity, treating patients in a hospital, selling drugs, or simply begging or re-selling small items on a street corner – a common practice in many developing sector countries.

Applying this approach, our 2020 study found that there are some 1.585 billion people worldwide who do not produce any physical economic value because, over the past half century and more, they have been dumped onto the human scrap heap by the British imperial system of the City of London and Wall Street—and barely survive from day to day. That is a 46% real unemployment rate.

Applying this approach, our 2020 study found that there are some 1.585 billion people worldwide who do not produce any physical economic value because, over the past half century and more, they have been dumped onto the human scrap heap by the British imperial system of the City of London and Wall Street—and barely survive from day to day. That is a 46% real unemployment rate.

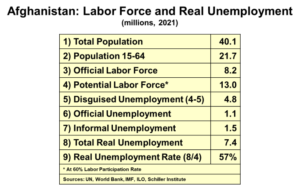

Applying a similar methodology to Afghanistan, using available statistics for 2021 from the UN, World Bank, IMF and ILO, we estimate – and I emphasize that this is only a first approximation, awaiting better data based on first-hand knowledge of the situation on the ground – that out of a total potential labor force of 13 million, some 7.4 million, or 57%, are in fact unemployed, i.e., not producing real physical-economic wealth. Here is how we derived that conclusion.

The official labor force for 2021 was 8.2 million people, according to the IMF, down from 9.1 million in 2020 – a sharp annual drop reflecting the overall collapse of the Afghan economy in the wake of the U.S. withdrawal, the rapid drop in international aid, and the theft of over $9 billion in Afghan central bank funds. . That official labor force of 8.2 million translates into a Labor Force Participation Rate (the total labor force as a percentage of the total population in the 15-64 age bracket) of 38% — a very low ratio even by developing sector standards, which averages closer to 60%. If Afghanistan were to have that same Labor Force Participation Rate of 60%, its “Industry and Labour, the Big Challenge” (3)

potential labor force would total 13.0 million. That fact strongly suggests that the difference between the two (13.0 – 8.2 = 4.8 million) are people either in the informal sector or otherwise functionally outside the national statistical accounts for available labor – a form of disguised unemployment from the standpoint of physical economy. It is also noteworthy that the average life expectancy in Afghanistan was only 62 in 2021, according to the World Bank. To arrive at a total figure for real unemployment, we have to add to those 4.8 million people, the 1.1 million officially counted as unemployed, as well as an estimate of 1.5 million out of the total number of people otherwise working in the informal economy or in unproductive “service” jobs. That brings total real unemployment in Afghanistan to about 7.4 million, out of a total potential, i.e., employable labor force of 13.0 million – for a 57% real unemployment rate.

potential labor force would total 13.0 million. That fact strongly suggests that the difference between the two (13.0 – 8.2 = 4.8 million) are people either in the informal sector or otherwise functionally outside the national statistical accounts for available labor – a form of disguised unemployment from the standpoint of physical economy. It is also noteworthy that the average life expectancy in Afghanistan was only 62 in 2021, according to the World Bank. To arrive at a total figure for real unemployment, we have to add to those 4.8 million people, the 1.1 million officially counted as unemployed, as well as an estimate of 1.5 million out of the total number of people otherwise working in the informal economy or in unproductive “service” jobs. That brings total real unemployment in Afghanistan to about 7.4 million, out of a total potential, i.e., employable labor force of 13.0 million – for a 57% real unemployment rate.

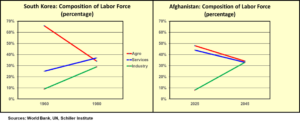

This is an all-too-familiar pattern among developing sector nations in terms of the sectoral composition of the labor force: overweight agricultural and services sectors, with a diminutive manufacturing and industrial base. This goes a long way to explaining the physical-economic low productivity of such economies.

It is instructive to see what occurred with other nations that once suffered from this same pattern, but were eventually able to achieve substantial industrialization.

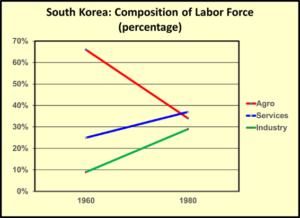

South Korea

Back in 1960, South Korea was a classically underdeveloped country, with 66% of its labor force in the agricultural sector, and only 9% in industry. It ranked 31st in the world in terms of GDP – which is an admittedly inadequate measure of real economic growth, which we use only for comparative purposes here. Twenty years later, South Korea was able to shift employment out of agriculture principally into industry, to the point that 29% of its labor force was in the industrial sector as of 1980 – more than tripling the 1960 percentage. With this dramatic shift towards industrialization, South Korea is today ranked 13th in the world in GDP.

A similar shift can be achieved in Afghanistan:

Over a 20-year horizon, for example from 2025 – 2045, it should be possible to increase the percentage of the labor force employed in industry to about a third of the total (from 8% today), while proportionately reducing the percentages in agriculture and services, down to about a third each, as well.

“Industry and Labour, the Big Challenge” (5)

The immediate objectives proposed for a five-year plan include:

- Triple employment in manufacturing, from about 500,000 today to 1.5 million by 2028;

- Create an additional 1.5 million new jobs in construction, especially of major infrastructure projects.

- Productively employ another 3 million workers who are today unemployed or trapped in the low-productivity informal sector of the economy.

Combined, these measures will cut real unemployment in half.

Prioritizing Industrial Employment

What are the priority areas in which to increase employment? In addition to food self-sufficiency, and related food and fiber processing sectors of manufacturing, there are a number of core industrial sectors that merit special attention.

Cement/concrete:

Cement/concrete is used to build every kind of basic infrastructure, from road culverts to housing, hospitals and factories.

We recommend a target of building a series of cement plants with a total combined production capacity of 2.5 to 3 million tons per year. Each plant requires approximately 20 months from greenfield to start of production.

Steel:

The annual steel output of Afghanistan, in the range of 33,000 metric tons as of 2018 – should be increased many times over.

Machinery and Machine Tools:

Machinery to make products ranging from vehicles to appliances to food processing, is a sector requiring top-down support to get established and take off on the scale needed.

To scale up across all types of manufacturing, and supply the parts to sustain their functioning, machine tools are essential. For the short term, machine tools will have to be imported to supply these needs. But at the same time, a dozen or so machine-tool parks should be established in key locations across the country, each with 10 to 30 workers, under the direction of a highly skilled machine tool operator/teacher. This will require some 200 quality machine tools.

Mining and metallurgy:

The resource base in Afghanistan is rich in minerals, ores, hydrocarbons and other valuable deposits, favorable to full-set industrial development. Afghanistan has an estimated 2.2 billion tons of iron ore reserves, placing the nation in the world’s top ten for extractable iron. The copper deposits are also immense. Of special value are the rare earth minerals, including lithium, tantalum, and beryllium. All these metals are necessary for modern electronics, medical appliances and high-technology uses.

In all of these extractive industries, it is important to engage in as much processing, smelting and advanced metallurgy as possible within Afghanistan – not only to have greater value added, but also to train the labor force to achieve increasing skill levels.

One useful example worth studying is the “Mutún Model” in Bolivia, which has one of the world’s largest iron ore deposits. Bolivia, like Afghanistan, is a mountainous, land-locked nation – its capital La Paz sits in the Andes mountains at an elevation of 3,650 meters above sea level, more than twice the elevation of Kabul’s 1,790! –, and it is also endowed with substantial mineral deposits. Like Afghanistan, Bolivia has often had those mineral riches looted by international financial interests, using debt as a mechanism.

Adapting such a “Mutún Model” to Afghanistan’s circumstances could provide the appropriate focus to greatly expanding the work of the Kabul Polytechnic University (KPU), as well as other such schools.

This higher-learning institution, considered the main center of educating engineers in Afghanistan, should be greatly expanded. Over the years, KPU has trained thousands of specialists in essential professions.

The wide-ranging areas of study include civil and mechanical engineering and construction, architecture, geology, exploration and mining, chemical technologies, engineering geodesy, autos and tractors, power supplies for industry, and many more.

KPU can become an important asset in Operation Ibn Sina, in particular in the all-important development goal of increasing the productive powers of labor.